Treadmill 101

“If you can't fly, then run, if you can't run, then walk, if you can't walk, then crawl, but whatever you do you have to keep moving forward.” – Martin Luther King, Jr.

When it comes to the single best exercise for cardiopulmonary patients, the treadmill is in a class by itself. There are several important reasons for this. First and foremost, as human beings, we need to walk. Second, the treadmill is highly controllable and customizable, meaning that you can set very specific workout parameters for speed, incline, and consequently, workload or MET level. Finally, the treadmill physically assists your walking and provides mechanical support for your breathing, thereby allowing you to maximize your overall workout.

Patients often remark that walking on a treadmill is different and, in some ways, easier than walking outside or even from one room to the next. Notice that with each step forward, the treadmill moves your feet to the back of the belt, decreasing the resistance of the ground. As a point of reference, walking outside on a flat surface is the equivalent of walking at approximately a 2% incline on the treadmill.

Another factor is that when you fix your upper extremities by holding on to the handrails, the treadmill becomes a closed chain activity and divides the workload among four limbs instead of two. In addition, closing the chain greatly improves respiratory mechanics, allowing the muscles of your thorax; chest, back, shoulders to work in their reverse action, further assisting with ribcage elevation and overall thoracic expansion, allowing you to take a deeper breath.

Although we have touched on exercise multiple times throughout this book, I have not yet given you the specifics of treadmill exercise that you want and need. At this point, I would like to introduce some tools that will help you develop the absolute best treadmill protocol for you so that you can achieve the very best results within each and every workout.

As always, please do not begin any exercise program without clearing it with your doctor first, ideally after a comprehensive cardiac workup but at a minimum, some form of clinical exercise evaluation.

How Hard Should I Work Out?

When it comes to treadmill activity, patients often ask me some version of the following questions: (1) how hard I should work out, and (2) what’s more important: speed or incline, and (3) what’s more important: time or distance. The answer is that they are all important and in fact, all directly related to and affected by one another. The longer you walk on the treadmill, the more mileage you will cover at a single speed. The faster you walk, the more mileage you will cover in the same amount of time.

However, when it comes to creating the most effective workout, that will not only produce the best results, but also have the greatest carryover to everyday life, MET Level (Measure of Exercise Tolerance or metabolic equivalent) is the most crucial (yet, frequently overlooked) factor. Also, when it comes to treadmill protocols and parameters, the MET is the great equalizer, allowing us to compare apples to apples and oranges to oranges.

As a quick review, one MET is equal to 3.5 mL of oxygen per kilogram of body weight per minute or the equivalent of your metabolic state at rest. This means that when you are at one met (think sitting quietly in a chair), your body consumes 3.5 milliliters of oxygen per minute for every kilogram (2.2 pounds) of your body weight. Activities at the two MET level would double your oxygen requirements to 7 mL of oxygen per kilogram of body weight per minute. Three METs would triple the workload and so on. You get the idea. As a point of reference, a workload of 1.1 METs to 2.9 METs is considered light, 3.0-5.9 METs is considered moderate and 6.0 METs or greater is considered vigorous activity.

Sadly, it is not only patients that are sometimes confused by this subject. Many healthcare professionals also struggle to understand how to create the most effective treadmill protocols and exercise goals for people with pulmonary conditions. In fact, if you read much of the classic literature pertaining to pulmonary rehabilitation, most people agree that patients feel less short of breath, can tolerate more activity and have a greater sense of confidence and wellbeing. However, most claims fall short of promising improved pulmonary function.

In contrast, my colleagues and I know that you can improve pulmonary function under the right conditions. However, as opposed to the traditional low-intensity long-duration exercise used in more traditional programs, we have consistently found that it takes moderate and high-intensity exercise if you want to improve pulmonary function. For all of these reasons, it is important for you to understand how to use MET level to your greatest advantage.

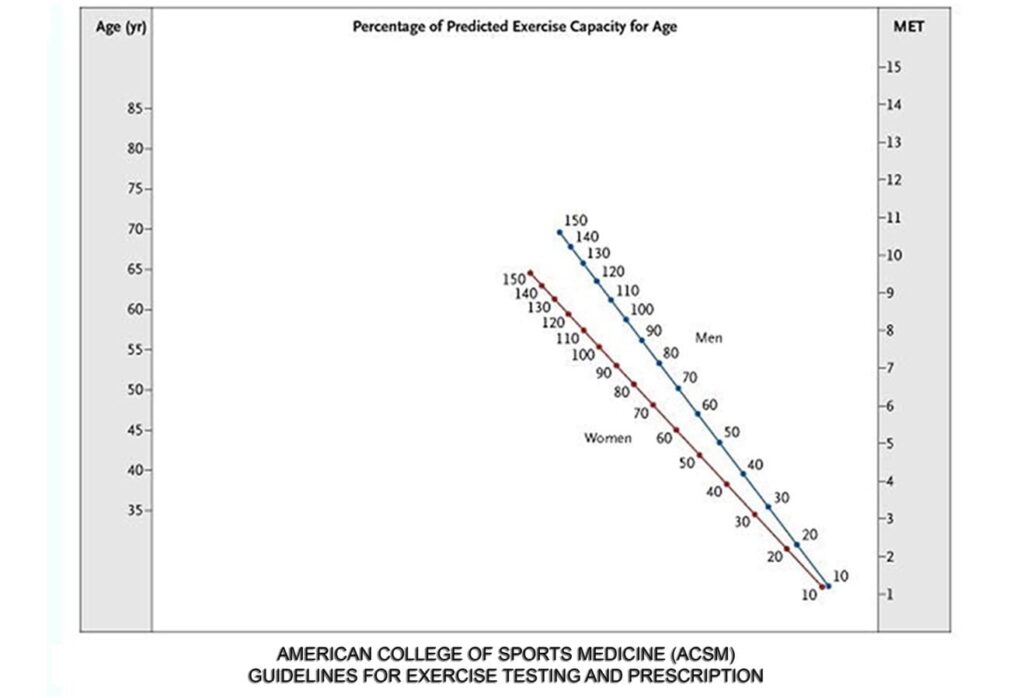

In this chapter, I will introduce you to two charts that we use at Pulmonary Wellness: the Treadmill MET Chart and the American College of Sports Medicine’s (ACSM) Age-Predicted Exercise Capacity (APEC Chart). Please do not be intimidated if they look complex at first. I promise after some explanation, they will make a lot of sense.

Treadmill MET Chart

The Treadmill MET Chart will tell you the MET Level for various combinations of speed and incline. The numbers across the bottom row of the chart represent speed in miles per hour (mph). The numbers in the first column on the left represent the percent incline (incline %). To determine the metabolic equivalent or MET Level, first find your speed along the bottom and then match it up with the corresponding incline. MET level is found at the intersection of speed and incline.

As an example, walking at 1.0 mph with no incline (0%) is equal to 1.8 METs. If we raise the speed to 1.6 mph, the MET level increases to 1.9 METs. If we then increase the incline to 3%, our MET level increases to 2.9 METs. You get the idea.

Here is another application. If you were to walk at 3.0 mph with a 0% incline, your level would be 3.3 METs. Now, three miles per hour may be too fast for many people (and too slow for others).

However, if you were to lower that speed to 1.6 mph (approximately half), you could still reach that same 3.3 MET level by adding a 5% incline. Essentially, what this chart demonstrates is that there are many ways to accomplish the same MET level. This is an extremely valuable resource that will allow you to tailor your treadmill activity for maximum results, while individualizing the program to address and adapt to your own particular circumstances and abilities.

As an example, individuals with Spinal Stenosis, Osteoarthritis and other musculoskeletal conditions may have a harder time walking on a steep incline. In that case, you can increase the speed to achieve your target-MET level. Alternatively, if you are 4’ 11” with short legs or have a neurological condition that affects your gait, maintaining a higher speed may be a challenge. In this case, you can walk at a slower speed with a higher incline to achieve your workout goal. Get it?

Age-Predicted Exercise Capacity (APEC) Chart

The ACSM’s Age-Predicted Exercise Capacity (APEC) chart will tell you the percentage of exercise capacity predicted for a healthy person of your age and gender. To use this chart, first find your age on the left side. Then, take a ruler or sheet of paper and place it on your age. Then move the other side of the ruler to the MET level that you are working at (based on the treadmill MET chart). The point at which the ruler or paper intersects either the red line (for women) or the blue line (for men) represents the percentage of your age-predicted exercise capacity.

Here is another application. If you want to work out at a specific percentage of your age- predicted maximum, match up your age with the percentage of maximum that you would like to achieve and then extend the line to find out the appropriate MET level.

I encourage you to share these charts with your doctors and pulmonary rehab providers. They may or may not be aware of or practice this protocol but at The Pulmonary Wellness & Rehabilitation Center, we know that the MET counts for everything!

Creating a Treadmill Protocol

My goal with this chapter is to help you understand how to create the most effective and practical treadmill protocol for you. However, while I can offer you general principles and strategies, I do not know your medical history and I have not had a chance to examine you or conduct any of my own testing to assess your abilities with respect to

abilities and goals. This is why it is so crucial for you to clear any exercise suggestions you may see here with your physician.

In addition, if you have any cardiovascular risk factors or are prone to desaturation (among other conditions), you should not exercise unsupervised, at least in the beginning. That being said, I am also a realist and as much as I would love to recommend a personalized exercise program for you, I realize that many readers may be setting out on this journey alone, whether it be due to lack of access to a rehab facility, insurance or other factors. Again, this is why it is crucial for you to speak with your doctor to ensure that you will be safe.

What if I don’t have a Treadmill?

To be clear, I’m not saying that you can’t get a good workout on a stationary bike or elliptical machine or even walking. These are all excellent alternatives. In fact, the best option is a cross training program in which you perform several different exercises within the same workout. But once again, if you want to choose the single best exercise that has the greatest chance of success, the treadmill would be my first choice, hands down.

Of course, if you do not have access to a treadmill, all is not lost. If that is your situation, then walk outside whenever possible. The MET chart can still guide you in estimating your goals. Try speeding up or slowing down and find someplace with a varied terrain where you can increase the intensity of your workout using hills and slopes for inclines.

Other Considerations

- Clear any and all exercise with your doctor. I cannot emphasize this enough. Ideally, I would like every patient to have a full physical examination as well as specific tests to assess cardiovascular risk such as a stress test with echocardiogram at a minimum. Under the right circumstances, exercise can be the best thing for you. Under the wrong circumstances, it can be the worst and as I have said before, when it comes to patient safety, I don’t like surprises.

- If in doubt, refer to number 1.

- Start slowly and progress gradually as tolerated. Like Goldilocks, we like our workouts just right. However, it will always be better to err on the side of caution and underdo it rather than overdo it. Doing too much can increase your chances of an acute cardiac event or the development of an overuse injury and sometimes, you may not feel the full impact of the workout until several hours or days later. As I say to my patients: “everything will be done to your tolerance. Each time you come back and tell us that you felt well after the last session we will gradually increase your time and intensity.”

- Think long-term and don’t overdo it. Let me put things in perspective for you. If you were to start off today walking on the treadmill at 1.0 mph and added .1 mile per hour per week, in a year, you would be walking at 6.2 mph. If you were to start off today walking on the treadmill at 0% incline and added .5% per week, in a year, you would be walking at 26% incline. Now, I am not suggesting that you will be walking at 6.2 mph with a 26% incline. I’m just trying to say you don’t have to do it all in the first week.

- Pay attention to warning signals. As I say to my patients: “If at any time during the workout, you feel tired, dizzy, short of breath, chest pain or pressure, or you simply want to stop the workout, let me know right away.” Since, I will not be with you, don’t let me know. If you are unsure, stop. This is not an excuse not to exercise. I’m just saying that if you see any red flags, take them seriously.

- Push yourself whenever possible. This may seem to contradict what I have just said in number 6. It doesn’t. What I am saying is that if your life requires 5 METs, you can work out at 2 until the cows come home but your life will not be much different. Use the charts to figure out what speed, incline, and MET level you should be working at.

- Wear comfortable clothing and supportive sneakers or walking shoes.

- Perform a gradual warm-up and cool-down. The body doesn’t like surprises. In other words, if you go from sitting in a chair to walking or running on the treadmill at your maximum capacity, your body can’t tell the difference between that and getting chased by a bear and it could respond as such in the form of higher heart rates, and blood pressures, increased shortness of breath and decreased oxygen saturation. Another way to think of your workout is like a flight. You want a nice gradual takeoff, a comfortable cruising altitude and a nice smooth landing.

- Don’t stand still when the treadmill stops. Most people’s inclination is to stand on the treadmill for a few seconds when the belt stops. However, this can cause you to become light-headed or dizzy and in extreme cases, you could pass out. The reason for this is that when you are exercising, the heart is pumping blood to the body and the calf muscles return the blood from the lower part of the body to the heart. When you stand still, the heart is still pumping and blood can pool in your lower extremities.

- Rely on your instruments. Buy a pulse oximeter and blood pressure cuff so that you can measure your vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure and oxygen saturation) before, during, and after exercise. You cannot always go by how you feel. And again, when it comes to safety, we don’t want to assume. We want to know.

- Do “the breathing.” Use controlled breathing techniques like abdominal breathing, pursed lip breathing and paced breathing. Time your breathing with your stepping. Breathe in, in, and blow- two, three, four (or whatever pattern works best for you).

- Use supplemental oxygen when necessary. During exercise, we like our patients to be at a minimum oxygen saturation of 93% and we will use as much oxygen as necessary to keep them there. If you drop below 90%, you need oxygen. And given the choice, I would much rather give you more oxygen and allow you to do a bigger workout than not give it to you and have your workout be limited due to desaturation. Remember that it is these big workouts that will allow for the greatest improvements.

- Take your short-acting bronchodilator (“rescue inhaler”) 10-15 minutes before exercise. Of course, you need to check with your physician on this one but again, our goal is the biggest workout possible, by any means necessary. So, if this will allow you to relax the airways, open up the lungs and have a better workout, go for it!

- Exercise Testing and Prescription: To be clear, all of our patients come to us by physician referral. In addition, before we begin any exercise, we do our own treadmill testing using the Bensen Treadmill Protocol, developed by one of my former colleagues, Brooke Bensen. This allows us to determine exactly where a patient is at that moment and to set up a program that is going to be safe and the most effective.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter For Upcoming Offers

- Be the first to know about new webinars, exclusive offers, and podcasts.